A hierarchy (Greek: hierarchia (ἱεραρχία), from hierarches, "leader of sacred rites") is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) in which the items are represented as being "above," "below," or "at the same level as" one another. Abstractly, a hierarchy is simply an ordered set or an acyclic directed graph.

A hierarchy can link entities either directly or indirectly, and either vertically or horizontally. The only direct links in a hierarchy, insofar as they are hierarchical, are to one's immediate superior or to one of one's subordinates, although a system that is largely hierarchical can also incorporate alternative hierarchies. Indirect hierarchical links can extend "vertically" upwards or downwards via multiple links in the same direction, following a path. All parts of the hierarchy which are not linked vertically to one another nevertheless can be "horizontally" linked through a path by traveling up the hierarchy to find a common direct or indirect superior, and then down again. This is akin to two co-workers or colleagues; each reports to a common superior, but they have the same relative amount of authority.

Degree of branching

Degree of branching refers to the number of direct subordinates or children an object has (equivalent to the number of vertices a node has). Hierarchies can be categorized based on the "maximum degree", the highest degree present in the system as a whole. Categorization in this way yields two broad classes: linear and branching.

In a linear hierarchy, the maximum degree is 1.[1] In other words, all of the objects can be visualized in a lineup, and each object (excluding the top and bottom ones) has exactly one direct subordinate and one direct superior. Note that this is referring to the objects and not the levels; every hierarchy has this property with respect to levels, but normally each level can have an infinite number of objects. An example of a linear hierarchy is the hierarchy of life.

In a branching hierarchy, one or more objects has a degree of 2 or more (and therefore the maximum degree is 2 or higher).[1] For many people, the word "hierarchy" automatically evokes an image of a branching hierarchy.[1] Branching hierarchies are present within numerous systems, including organizations and classification schemes. The broad category of branching hierarchies can be further subdivided based on the degree.

A flat hierarchy is a branching hierarchy in which the maximum degree approaches infinity, i.e., with a wide span.[2] Most often, systems intuitively regarded as hierarchical have at most a moderate span. Therefore, a flat hierarchy is often not viewed as a hierarchy at all at first blush. For example, diamonds and graphite is a flat hierarchy of numerous carbon atoms which can be further decomposed into subatomic particles.

An overlapping hierarchy is a branching hierarchy in which at least one object has two parent objects.[1] For example, a graduate student can have two co-supervisors to whom the student reports directly and equally, and who have the same level of authority within the university hierarchy (i.e., they have the same position or tenure status

Maslow's hierarchy of human needs. This is an example of a hierarchy visualized with a triangle diagram.

A hierarchy is typically depicted as a pyramid, where the height of a level represents that level's status and width of a level represents the quantity of items at that level relative to the whole. For example, the few Directors of a company could be at the apex, and the base could be thousands of people who have no subordinates.

These pyramids are typically diagrammed with a tree or triangle diagram (but note that not all triangle/pyramid diagrams are hierarchical), both of which serve to emphasize the size differences between the levels. An example of a triangle diagram appears to the right. An organizational chart is the diagram of a hierarchy within an organization, and is depicted in tree form below.

More recently, as computers have allowed the storage and navigation of ever larger data sets, various methods have been developed to represent hierarchies in a manner that makes more efficient use of the available space on a computer's screen. Examples include fractal maps, TreeMaps and Radial Trees.

plain English, a hierarchy can be thought of as a set in which:[1]

"Hierarchy" is particularly used to refer to a poset in which the classes are organized in terms of increasing complexity.

A nested hierarchy or inclusion hierarchy is a hierarchical ordering of nested sets.[8] The concept of nesting is exemplified in Russian matryoshka dolls. Each doll is encompassed by another doll, all the way to the outer doll. The outer doll holds all of the inner dolls, the next outer doll holds all the remaining inner dolls, and so on. Matryoshkas represent a nested hierarchy where each level contains only one object, i.e., there is only one of each size of doll; a generalized nested hierarchy allows for multiple objects within levels but with each object having only one parent at each level. The general concept is both demonstrated and mathematically formulated in the following example:

A nested hierarchy or inclusion hierarchy is a hierarchical ordering of nested sets.[8] The concept of nesting is exemplified in Russian matryoshka dolls. Each doll is encompassed by another doll, all the way to the outer doll. The outer doll holds all of the inner dolls, the next outer doll holds all the remaining inner dolls, and so on. Matryoshkas represent a nested hierarchy where each level contains only one object, i.e., there is only one of each size of doll; a generalized nested hierarchy allows for multiple objects within levels but with each object having only one parent at each level. The general concept is both demonstrated and mathematically formulated in the following example:

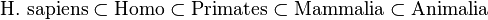

Nested hierarchies are the organizational schemes behind taxonomies and systematic classifications. For example, using the original Linnaean taxonomy (the version he laid out in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae), a human can be formulated as:[9]

means x is a subset of y but is not equal to y.

means x is a subset of y but is not equal to y.

A general example of a containment hierarchy is demonstrated in class inheritance in object-oriented programming.

Two types of containment hierarchies are the subsumptive containment hierarchy and the compositional containment hierarchy. A subsumptive hierarchy "subsumes" its children, and a compositional hierarchy is "composed" of its children. A hierarchy can also be both subsumptive and compositional.[10]

The compositional hierarchy that every person encounters at every moment is the hierarchy of life. Every person can be reduced to organ systems, which are composed of organs, which are composed of tissues, which are composed of cells, which are composed of molecules, which are composed of atoms. In fact, the last two levels apply to all matter, at least at the macroscopic scale. Moreover, each of these levels inherit all the properties of their children.

In this particular example, there are also emergent properties—functions that are not seen at the lower level (e.g., cognition is not a property of neurons but is of the brain)—and a scalar quality (molecules are bigger than atoms, cells are bigger than molecules, etc.). Both of these concepts commonly exist in compositional hierarchies, but they are not a required general property. These level hierarchies are characterized by bi-directional causation.[8] Upward causation involves lower-level entities causing some property of a higher level entity; children entities may interact to yield parent entities, and parents are composed at least partly by their children. Downward causation refers to the effect that the incorporation of entity x into a higher-level entity can have on x's properties and interactions. Furthermore, the entities found at each level are autonomous.

While the above examples are often clearly depicted in a hierarchical form and are classic examples, hierarchies exist in numerous systems where this branching structure is not immediately apparent. For example, all postal code systems are necessarily hierarchical. Using the Canadian postal code system, the top level's binding concept is the "postal district", and consists of 18 objects (letters). The next level down is the "zone", where the objects are the digits 0–9. This is an example of an overlapping hierarchy, because each of these 10 objects has 18 parents. The hierarchy continues downward to generate, in theory, 7,200,000 unique codes of the format A0A 0A0. Most library classification systems are also hierarchical. The Dewey Decimal System is regarded as infinitely hierarchical because there is no finite bound on the number of digits can be used after the decimal point.[17]

In a reverse hierarchy, the conceptual pyramid of authority is turned upside-down, so that the apex is at the bottom and the base is at the top. This model represents the idea that members of the higher rankings are responsible for the members of the lower rankings.

In this system, the three (or four with Algonquian languages) persons are placed in a hierarchy of salience. To distinguish which is subject and which object, inverse markers are used if the object outranks the subject.

In music, the structure of a composition is often understood hierarchically (for example by Heinrich Schenker (1768–1835, see Schenkerian analysis), and in the (1985) Generative Theory of Tonal Music, by composer Fred Lerdahl and linguist Ray Jackendoff). The sum of all notes in a piece is understood to be an all-inclusive surface, which can be reduced to successively more sparse and more fundamental types of motion. The levels of structure that operate in Schenker's theory are the foreground, which is seen in all the details of the musical score; the middle ground, which is roughly a summary of an essential contrapuntal progression and voice-leading; and the background or Ursatz, which is one of only a few basic "long-range counterpoint" structures that are shared in the gamut of tonal music literature.

The pitches and form of tonal music are organized hierarchically, all pitches deriving their importance from their relationship to a tonic key, and secondary themes in other keys are brought back to the tonic in a recapitulation of the primary theme. Susan McClary connects this specifically in the sonata-allegro form to the feminist hierarchy of gender (see above) in her book Feminine Endings, even pointing out that primary themes were often previously called "masculine" and secondary themes "feminine."

In all of these random examples, there is an asymmetry of 'compositional' significance between levels of structure, so that small parts of the whole hierarchical array depend, for their meaning, on their membership in larger parts.

In the work of diverse theorists such as William James (1842–1910), Michel Foucault (1926–1984) and Hayden White, important critiques of hierarchical epistemology are advanced. James famously asserts in his work "Radical Empiricism" that clear distinctions of type and category are a constant but unwritten goal of scientific reasoning, so that when they are discovered, success is declared. But if aspects of the world are organized differently, involving inherent and intractable ambiguities, then scientific questions are often considered unresolved.

Feminists, Marxists, anarchists, communists, critical theorists and others, all of whom have multiple interpretations, criticize the hierarchies commonly found within human society, especially in social relationships. Hierarchies are present in all parts of society: in businesses, schools, families, etc. These relationships are often viewed as necessary. However, feminists, Marxists, critical theorists and others analyze hierarchy in terms of the values and power that it arbitrarily assigns to one group over another.

A hierarchy can link entities either directly or indirectly, and either vertically or horizontally. The only direct links in a hierarchy, insofar as they are hierarchical, are to one's immediate superior or to one of one's subordinates, although a system that is largely hierarchical can also incorporate alternative hierarchies. Indirect hierarchical links can extend "vertically" upwards or downwards via multiple links in the same direction, following a path. All parts of the hierarchy which are not linked vertically to one another nevertheless can be "horizontally" linked through a path by traveling up the hierarchy to find a common direct or indirect superior, and then down again. This is akin to two co-workers or colleagues; each reports to a common superior, but they have the same relative amount of authority.

Degree of branching

Degree of branching refers to the number of direct subordinates or children an object has (equivalent to the number of vertices a node has). Hierarchies can be categorized based on the "maximum degree", the highest degree present in the system as a whole. Categorization in this way yields two broad classes: linear and branching.

In a linear hierarchy, the maximum degree is 1.[1] In other words, all of the objects can be visualized in a lineup, and each object (excluding the top and bottom ones) has exactly one direct subordinate and one direct superior. Note that this is referring to the objects and not the levels; every hierarchy has this property with respect to levels, but normally each level can have an infinite number of objects. An example of a linear hierarchy is the hierarchy of life.

In a branching hierarchy, one or more objects has a degree of 2 or more (and therefore the maximum degree is 2 or higher).[1] For many people, the word "hierarchy" automatically evokes an image of a branching hierarchy.[1] Branching hierarchies are present within numerous systems, including organizations and classification schemes. The broad category of branching hierarchies can be further subdivided based on the degree.

A flat hierarchy is a branching hierarchy in which the maximum degree approaches infinity, i.e., with a wide span.[2] Most often, systems intuitively regarded as hierarchical have at most a moderate span. Therefore, a flat hierarchy is often not viewed as a hierarchy at all at first blush. For example, diamonds and graphite is a flat hierarchy of numerous carbon atoms which can be further decomposed into subatomic particles.

An overlapping hierarchy is a branching hierarchy in which at least one object has two parent objects.[1] For example, a graduate student can have two co-supervisors to whom the student reports directly and equally, and who have the same level of authority within the university hierarchy (i.e., they have the same position or tenure status

[edit] History of the term

The first use of the English word "hierarchy" cited by the Oxford English Dictionary was in 1880, when it was used in reference to the three orders of three angels as depicted by Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (5th–6th centuries). Pseudo-Dionysius used the related Latin word (hierarchia) both in reference to the celestial hierarchy and the ecclesiastical hierarchy.[3] His term is derived from the Greek term "ἱεραρχία" meaning "rule by priests" (from "ἱεράρχης" – ierarches, meaning "president of sacred rites, high-priest"[4] and that from "ἱερεύς" – iereus, "priest"[5] + "ἀρχή" – arche, amongst others "first place or power, rule"[6]), and Dionysius is credited with first use of it as an abstract noun. Since hierarchical churches, such as the Roman Catholic (see Catholic Church hierarchy) and Eastern Orthodox churches, had tables of organization that were "hierarchical" in the modern sense of the word (traditionally with God as the pinnacle or head of the hierarchy), the term came to refer to similar organizational methods in secular settings.Maslow's hierarchy of human needs. This is an example of a hierarchy visualized with a triangle diagram.

A hierarchy is typically depicted as a pyramid, where the height of a level represents that level's status and width of a level represents the quantity of items at that level relative to the whole. For example, the few Directors of a company could be at the apex, and the base could be thousands of people who have no subordinates.

These pyramids are typically diagrammed with a tree or triangle diagram (but note that not all triangle/pyramid diagrams are hierarchical), both of which serve to emphasize the size differences between the levels. An example of a triangle diagram appears to the right. An organizational chart is the diagram of a hierarchy within an organization, and is depicted in tree form below.

More recently, as computers have allowed the storage and navigation of ever larger data sets, various methods have been developed to represent hierarchies in a manner that makes more efficient use of the available space on a computer's screen. Examples include fractal maps, TreeMaps and Radial Trees.

[edit] Informal representation

plain English, a hierarchy can be thought of as a set in which:[1]

- No element is superior to itself, and

- One element, the hierarch, is superior to all of the other elements in the set.

[edit] Mathematical representation

Main article: Hierarchy (mathematics)

Mathematically, in its most general form, a hierarchy is a partially ordered set or poset.[7] The system in this case is the entire poset, which is constituted of elements. Within this system, each element shares a particular unambiguous property. Objects with the same property value are grouped together, and each of those resulting levels is referred to as a class."Hierarchy" is particularly used to refer to a poset in which the classes are organized in terms of increasing complexity.

[edit] Subtypes

[edit] Nested hierarchy

Matryoshka dolls, also known as nesting dolls or Russian dolls. Each doll is encompassed inside another until the smallest one is reached. This is the concept of nesting. When the concept is applied to sets, the resulting ordering is a nested hierarchy.

Nested hierarchies are the organizational schemes behind taxonomies and systematic classifications. For example, using the original Linnaean taxonomy (the version he laid out in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae), a human can be formulated as:[9]

[edit] Containment hierarchy

A containment hierarchy is a direct extrapolation of the nested hierarchy concept. All of the ordered sets are still nested, but every set must be "strict"—no two sets can be identical. The shapes example above can be modified to demonstrate this: means x is a subset of y but is not equal to y.

means x is a subset of y but is not equal to y.A general example of a containment hierarchy is demonstrated in class inheritance in object-oriented programming.

Two types of containment hierarchies are the subsumptive containment hierarchy and the compositional containment hierarchy. A subsumptive hierarchy "subsumes" its children, and a compositional hierarchy is "composed" of its children. A hierarchy can also be both subsumptive and compositional.[10]

[edit] Subsumptive containment hierarchy

A subsumptive containment hierarchy is a classification of objects from the general to the specific. Other names for this type of hierarchy are "compositional hierarchy", "taxonomic hierarchy" and "IS-A hierarchy".[7][11][12] The last term describes the relationship between each level—a lower-level object "is a" member of the higher class. The taxonomical structure outlined above is a subsumptive containment hierarchy, as are all systematic naming schemes. Using again the example of Linnaean taxonomy, it can be seen that an object that is part of the level Mammalia "is a" member of the level Animalia; more specifically, a human "is a" primate, a primate "is a" mammal, and so on. A subsumptive hierarchy can also be defined abstractly as a hierarchy of "concepts".[12] For example, with the Linnaean hierarchy outlined above, an entity name like Animalia is a way to group all the species that fit the conceptualization of an animal.[edit] Compositional containment hierarchy

A compositional containment hierarchy is an ordering of the parts that make up a system—the system is "composed" of these parts.[13] Most engineered structures, whether natural or artificial, can be broken down in this manner.The compositional hierarchy that every person encounters at every moment is the hierarchy of life. Every person can be reduced to organ systems, which are composed of organs, which are composed of tissues, which are composed of cells, which are composed of molecules, which are composed of atoms. In fact, the last two levels apply to all matter, at least at the macroscopic scale. Moreover, each of these levels inherit all the properties of their children.

In this particular example, there are also emergent properties—functions that are not seen at the lower level (e.g., cognition is not a property of neurons but is of the brain)—and a scalar quality (molecules are bigger than atoms, cells are bigger than molecules, etc.). Both of these concepts commonly exist in compositional hierarchies, but they are not a required general property. These level hierarchies are characterized by bi-directional causation.[8] Upward causation involves lower-level entities causing some property of a higher level entity; children entities may interact to yield parent entities, and parents are composed at least partly by their children. Downward causation refers to the effect that the incorporation of entity x into a higher-level entity can have on x's properties and interactions. Furthermore, the entities found at each level are autonomous.

[edit] Contexts and applications

Almost every system within the world is arranged hierarchically.[14] By their common definitions, every nation has a government and every government is hierarchical.[15][16] Socioeconomic systems are stratified into a social hierarchy (the social stratification of societies), and all systematic classification schemes (taxonomies) are hierarchical. Most organized religions, regardless of their internal governance structures, operate as a hierarchy under God. Many Christian denominations have an autocephalous ecclesiastical hierarchy of leadership. Families are viewed as a hierarchical structure in terms of cousinship (e.g., first cousin once removed, second cousin, etc.), ancestry (as depicted in a family tree) and inheritance (succession and heirship). All the requisites of a well-rounded life and lifestyle can be organized using Maslow's hierarchy of human needs. Learning must often follow a hierarchical scheme—to learn differential equations one must first learn calculus; to learn calculus one must first learn elementary algebra; and so on. Even nature itself has its own hierarchies, as demonstrated in numerous schemes such as Linnaean taxonomy, the organization of life, and biomass pyramids. Hierarchies are so infused into daily life that they are viewed as trivial.[1][14]While the above examples are often clearly depicted in a hierarchical form and are classic examples, hierarchies exist in numerous systems where this branching structure is not immediately apparent. For example, all postal code systems are necessarily hierarchical. Using the Canadian postal code system, the top level's binding concept is the "postal district", and consists of 18 objects (letters). The next level down is the "zone", where the objects are the digits 0–9. This is an example of an overlapping hierarchy, because each of these 10 objects has 18 parents. The hierarchy continues downward to generate, in theory, 7,200,000 unique codes of the format A0A 0A0. Most library classification systems are also hierarchical. The Dewey Decimal System is regarded as infinitely hierarchical because there is no finite bound on the number of digits can be used after the decimal point.[17]

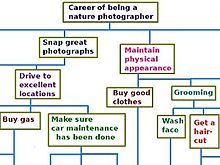

A simple organizational hierarchy depicted in the form of a tree. Diagrams like this are called organizational charts.

[edit] Organizations

Main articles: Organizational structure and Hierarchical organization

Organizations can be structured using a hierarchy. In an organizational hierarchy, there is a single person or group with the most power and authority, and each subsequent level represents a lesser authority. Most organizations are structured in this manner, including governments, companies, militia and organized religions. The units or persons within an organization are depicted hierarchically in an organizational chart.In a reverse hierarchy, the conceptual pyramid of authority is turned upside-down, so that the apex is at the bottom and the base is at the top. This model represents the idea that members of the higher rankings are responsible for the members of the lower rankings.

[edit] Computer graphic imaging (CGI)

Within most CGI and computer animation programs is the use of hierarchies. On a 3D model of a human, the chest is a parent of the upper left arm, which is a parent of the lower left arm, which is a parent of the hand. This is used in modeling and animation of almost everything built as a 3D digital model.[edit] Hierarchical verbal alignment

Main article: Direct–inverse language

In some languages, such as Cree and Mapudungun, subject and object on verbs are distinguished not by different subject and object markers, but via a hierarchy of persons.In this system, the three (or four with Algonquian languages) persons are placed in a hierarchy of salience. To distinguish which is subject and which object, inverse markers are used if the object outranks the subject.

In music, the structure of a composition is often understood hierarchically (for example by Heinrich Schenker (1768–1835, see Schenkerian analysis), and in the (1985) Generative Theory of Tonal Music, by composer Fred Lerdahl and linguist Ray Jackendoff). The sum of all notes in a piece is understood to be an all-inclusive surface, which can be reduced to successively more sparse and more fundamental types of motion. The levels of structure that operate in Schenker's theory are the foreground, which is seen in all the details of the musical score; the middle ground, which is roughly a summary of an essential contrapuntal progression and voice-leading; and the background or Ursatz, which is one of only a few basic "long-range counterpoint" structures that are shared in the gamut of tonal music literature.

The pitches and form of tonal music are organized hierarchically, all pitches deriving their importance from their relationship to a tonic key, and secondary themes in other keys are brought back to the tonic in a recapitulation of the primary theme. Susan McClary connects this specifically in the sonata-allegro form to the feminist hierarchy of gender (see above) in her book Feminine Endings, even pointing out that primary themes were often previously called "masculine" and secondary themes "feminine."

[edit] Ethics, behavioral psychology, philosophies of identity

In ethics, various virtues are enumerated and sometimes organized hierarchically according to certain brands of virtue theory.

In all of these random examples, there is an asymmetry of 'compositional' significance between levels of structure, so that small parts of the whole hierarchical array depend, for their meaning, on their membership in larger parts.

In the work of diverse theorists such as William James (1842–1910), Michel Foucault (1926–1984) and Hayden White, important critiques of hierarchical epistemology are advanced. James famously asserts in his work "Radical Empiricism" that clear distinctions of type and category are a constant but unwritten goal of scientific reasoning, so that when they are discovered, success is declared. But if aspects of the world are organized differently, involving inherent and intractable ambiguities, then scientific questions are often considered unresolved.

Feminists, Marxists, anarchists, communists, critical theorists and others, all of whom have multiple interpretations, criticize the hierarchies commonly found within human society, especially in social relationships. Hierarchies are present in all parts of society: in businesses, schools, families, etc. These relationships are often viewed as necessary. However, feminists, Marxists, critical theorists and others analyze hierarchy in terms of the values and power that it arbitrarily assigns to one group over another.